Many thanks to Dan Williams for sending in this article taken from a 1971 edition of the American publication “Graphical Arts Monthly.” It explores how viable a small letterpress print shop was in the early 1970s.

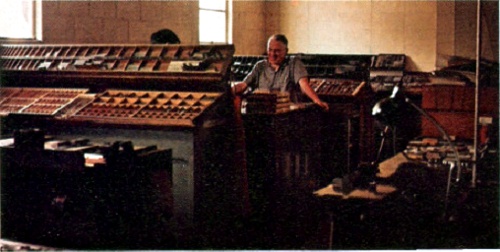

IS LETTERPRESS dead for the small printer? Edgecombe Printer in Kalamazoo, Mich, is a good example of a shop that is making a profit with letterpress in competition with offset.

When asked why he was staying in letterpress, Francis Edgecombe, owner of Edgecombe/ Printer, replied, “We feel that we have a greater opportunity with letterpress, since only a few are practicing it. We are concentrating on doing what many others have forgotten how to do. And, by continuing with letterpress, we don’t have the feeling that we are merely one litho printer competing with many others in the same field.”

Continuing, Francis said, “I prefer to stay in letterpress since I like it and believe I can do better with it. It lends itself well to a small operation such as we have, Some people believe I am a die-hard and can’t see the offset ‘wave of the future!’ but it isn’t this way.

We have shown that we can do quality work for customers, in a reasonable length of time, and at prices that are competitive with offset It all depends on the kind of job. We do well with certain jobs, and our offset friends do well with others. There is a field for both processes, We have seen jobs done offset that we felt would have fit letterpress better, and the reverse is also true. We sometimes refer customers to an offset shop when we feel that a particular job should be done that way.”

Edgecombe declared that he could in many cases be competitive with offset, or even lower in cost, providing that all of the preparatory costs are included in the offset price. He mentioned that some offset shops give a lower quote on “camera-ready” Copy, and the customer finds out later that certain preparatory costs must be added to obtain the total cost of the job.

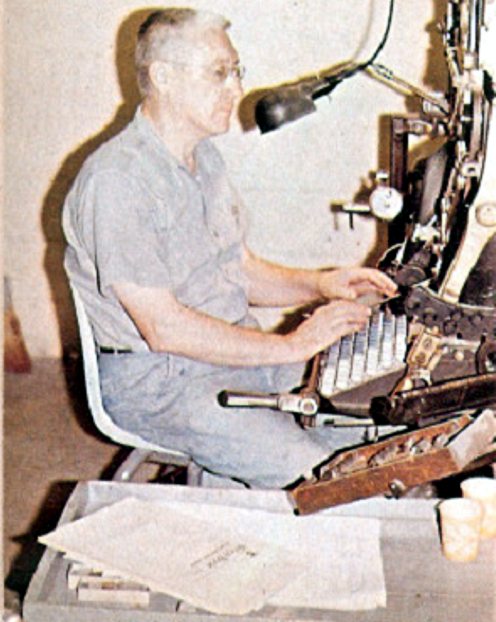

The two Linotypes at Edgecombe/Printer are good examples of the fine craftsmanship of Francis Edgecombe.

Both are Model 9 machines with which he has been familiar since the 1920s. The original base on the older of the two dates from 1919, but the face plate, distributor, and magazine frame are from the 1930s.

Francis updated the machine with these things, and declares that it still produces perfect slugs. He points out that the secret to this is good maintenance – and, of course, he takes care of this himself.

The other Linotype is one of the last of the Model 9s to be manufactured by Linotype.

The plant sets all of the type for jobs printed, either handset or Linotype. It also sells some to outsiders. “I can recall,” said Francis, “when I was learning to use foundry type in high school, that the ‘experts’ predicted we were wasting our time, since it would be obsolete in 10, 15, or X years, and be replaced entirely by hot metal. Now many commercial printers deplore the use of handset type in schools, since they say that the photocomp machines are going to take over the industry and revolutionize it.

This sounds like a repeat of the old record, with slightly different wording, doesn’t it? As a matter of fact, handset type is still here and will be as long as the finest work can be done with it.