The final flowering of the linecaster

By: BRUCE ANDERTON

AT the start of the 1960s hot metal composition was still the major source of typesetting in many branches of the printing industry, and though much thought and effort was being expended in developing replacements using photographic techniques, the old order still reigned supreme in many areas and the major manufacturers—Linotype, Intertype, Monotype and Ludlow—were still introducing new machines and typefaces and providing spares for their hot metal systems.

In America Mergenthaler Linotype and Harris-Intertype had introduced new linecasters which were designed to be driven from tape and were thus faster-running—normally operating at around 12 lines per minute on newspaper measures of 11½ems or thereabouts. Anyone who has seen such machines in operation will have been impressed by the speeded-up production rates compared to manually-operated equivalents.

Elektrons & Monarchs

In the newspaper field especially, such increased productivity was welcomed by managements worldwide. Leading examples of such equipment were Linotype’s “Elektron”, which incorporated much new engineering in its design, and Intertype’s “Monarch”, which although streamlined in appearance was in reality a linecaster retaining traditional features but speeded-up to accommodate the faster casting speeds now being demanded; its major surprise feature was in fact a deletion—one version could be obtained which did not have a keyboard, something that was no longer necessary when the machine spent all its working hours being driven by tape on the teletypesetter (TTS) system.

Thus it will be noted that the major influence in linecaster development came from the USA—but on this side of the Atlantic there was also development work afoot in the hot metal field, with Linotype & Machinery of Altrincham, Cheshire (English Linotype) ready to introduce a new four-magazine variant of its successful high-speed Model 79, whilst in Germany Mergenthaler Linotype GmbH (German Linotype) had a much more ambitious line-up of no less than six new models waiting to be launched: the “Neue Linie” or “New Line” range. Was it too good to be true?

Alas, it would appear so. Mergenthaler Linotype in the US, having spent a great deal of money on developing and manufacturing the Elektron, was anxious to sell it wherever it could on a worldwide basis and word was sent to the English and German companies to hold back from announcing their new machines and to offer the Elektron to all prospective customers wishing to buy new hot metal equipment. Thus the 794 in England and the “New Line” machines in Germany were sidelined and the Elektron was promoted as a suitable alternative to prospective customers, many of whom did not really need such a complicated and high-speed machine, and of course they also did not want to pay the increased prices being demanded.

Unfortunately, the all-new Elektron in its original form had far too many faults and what I would call “under-engineered” features which very soon began to act against it and it soon gained a reputation for unreliability. (As an aside I would quote the experience of one company I worked for which installed an Elektron which was only ever going to be operated manually on general jobbing work and would thus never be a 12-lines-a-minute wonder. It created so many problems for its operator that he eventually suffered a nervous breakdown and as a result of the constant mechanical failures it was arranged with L&M at Altrincham that the machine would be returned in part-exchange for a new Model 78, which was really all that had been needed in the first place! When I joined the company some years later all the setting was done on two Model 78s.)

Agreement for supply of 500 Elektrons

In 1966 an article appeared in L&M News, the house journal of Linotype & Machinery, which stated that an agreement had been signed between the German and English Linotype companies for the manufacture and supply by L&M of no less than five hundred Elektrons over a seven-year period, with an initial batch of 60 machines then being in course of delivery to Germany.

Whether this order was ever fulfilled—and to what extent—is not known, but it does highlight the lengths to which the American parent company was prepared to go in order to promote its problem child, for despite modifications carried out to the design by L&M engineers which made the Elektron much more reliable than had previously been the case, there were still far too many novelties which were constantly leading to unreliability “in the field” in a machine marketed as being capable of constant high speed operation, where any design defects could soon lead to unacceptable periods of “downtime” or even complete shutdown (a newspaper establishment where I worked acquired an Elektron which had an extremely short “working” life as a tape-operated machine before being part-exchanged for a new Model 78SM which was operated manually on display advertisement setting, an area completely unsuited to TTS operation).

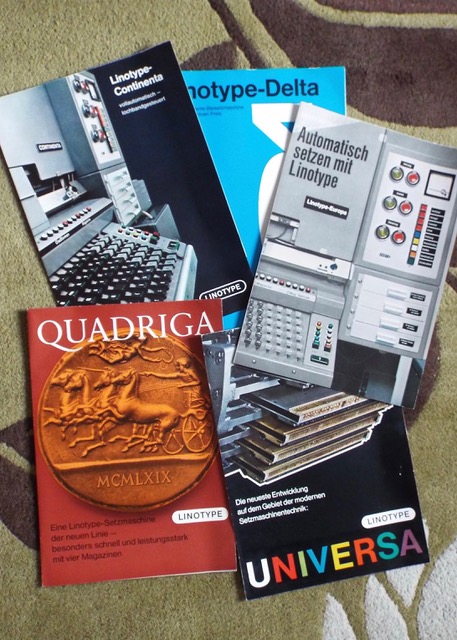

It would appear that 1966 marked a turning point in the Battle of the Elektron and it may well have been the time when the English and German companies were allowed to start marketing their own products again (I believe that it had been the case that they had been able to continue marketing machines that did not compete with or challenge the Elektron, thus both concerns were able to continue manufacturing and selling existing linecasters to customers not needing to be on the cutting edge of technology). Now the coast was clear for the Germans to launch what was probably the most exciting range of advanced linecasting machines ever built—the “New Line”.

Take a look at the “Related Pages” menu to see details and pictures of the individual models.

Linotype fan? Don’t miss the Linotype Chat section of the Metal Type Forum.